|

| Negroid English/Saxon coin |

In 1009 an enormous army, sent by King Swein of Denmark, arrived in England to depose Ethelred. Although the English bought the invaders off in 1012, the following year Swein led another invasion. Much of the demoralised English nation submitted to his rule. Ethelred resisted from London for some months, then finally fled to Normandy. After Swein died suddenly in February 1014, Ethelred was reinstated as king. His rule was challenged by Cnut, Swein's younger son, and apparently by his own son Edmund Iron-sides.

Cnut's first campaign misfired, and he retreated to Denmark, only to return to England with a new army in 1015. Ethelred and Edmund joined forces against the invader early in 1016 at London. But on April 23, 1016, Ethelred died. Edmund succeeded him and struggled on for a few months. However, by the end of the year Edmund too was dead, and Cnut became the ruler of England. Above: Negroid English/Saxon coin, minted in England, between the 10th and 11th centuries.

Canute or Cnut the Great was born circa 985- 995, the son of King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark, the identity of his mother is uncertain, although it is likely that she was a Slavic princess, daughter of Mieszko I of Poland. Canute was to become the ruler of an empire which, at its height, included England, Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden.

Canute was praised in Norse poetry as a formidable Viking warrior. He is described in the Knýtlinga saga as being 'exceptionally tall and strong, and the handsomest of men, all except for his nose, that was thin, high set, and rather hooked. He had a fair complexion none the less, and a fine, thick head of hair. His eyes were better than those of other men, both the more handsome and the keener of their sight'.

Emma of Normandy: Canute had supported his father against the Saxon King Ethelred the Redeless . Sweyn established himself on England's throne and Ethelred was forced to flee to Normandy, where he sought refuge with his wife's relatives. On the death of Sweyn Forkbeard in 1014, Ethelred returned to England and Canute was forced to withdraw to Denmark. There, he gathered his forces, returning to England in 1015 when he managed to gain control of virtually the whole country, except for the city of London.

On the death of the ineffectual Ethelred II in 1016, the Londoners chose his son Edmund Ironside as king, but the Witan opted for Canute. Following a series of engagements with Edmund, Canute defeated him at the Battle of Assandun, which was fought at either Ashingdon, in south-east, or Ashdon, in north-west Essex. A treaty was drawn up, partitioning the country which would remain in force until the death of one of the participants to the treaty, at which time all lands would revert to the survivor. Edmund II died a month later on 30 November 1016. Canute then became the acknowledged King of England, his coronation took place in London, at Christmas.

|

| Emma |

In what was considered a conciliatory gesture at the time, he repudiated his wife, Elgiva and married Ethelred's widow, Emma of Normandy. He became King of Denmark in 1019 and of Norway 1028, making him ruler of an Empire surrounding the North Sea. Following his conversion to Christianity, Canute became an avid protector of the church. He patronised abbeys, promoted leaders of the English church and was acknowledged by the Pope as the first Viking to become a Christian King. He embarked on a pilgrimage to Rome in 1027, displaying great reverence and humility. On his return to England he swore to his Saxon subjects that he would govern with mercy and justice.

Canute divided England into four distinct areas for administrative purposes. Wessex remained the seat of government and was ruled directly by himself. East Anglia was placed under a deputy, Earl Thurkill. The fickle and treacherous Edric Streona was rewarded for his services by being appointed Earl of Mercia. His kinsman, Eric became virtual viceroy of Northumbria.

Edric Streona was not to enjoy his new exalted position for long, considering himself to have not been amply rewarded by Canute, he quarrelled with the King. In a rage, Streona claimed that it was entirely due to his timely desertion of Edmund Ironside that Canute had acquired the throne. The wary Canute replied that a man who betrayed one master was likely to do the same to another. As Streona argued with the King, Eric of Northumbria stepped forward and struck him with his battle-axe. His body was slung into the Thames and his head placed on a spike on London Bridge.

King CanuteIn the early part of his reign Canute resorted to harsh measures to maintain his position, he had some of his prominent English rivals outlawed or killed, and engineered the death of Edmund Ironside's brother, he pursued Edmund's children forcing them to flee England for the safety of Hungary. But within a few years, when his position became safer, he adopted a fairer policy, and allowed more Saxons into positions of power.

The famous story that he was so vain he allowed himself to be convinced by flattering courtiers that he could hold back the tide is one of the chief events of the reign for which he appears to be remembered. In fact the old story of Canute and the waves is apocryphal and is first recorded by Henry of Huntingdon in his twelfth century Chronicle of the History of England.

|

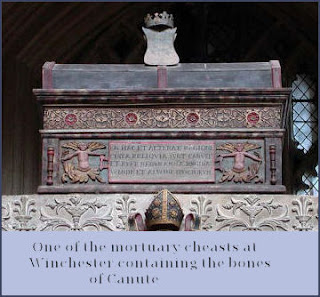

| Mortuary Chest |

His insistence that the kingdom should continue to be ruled by the laws laid down by Edgar the Peaceful lead to a growth in his popularity and he made his own additions to these, forbidding heathen practices. After initial raids, Malcolm II, King of Scots, recognised the over-lordship of Canute. Peace with Scotland was established for the remainder of his reign.

King Canute died on 12th November 1035 at Shaftsbury in Dorset, aged around 40 and was buried at Winchester Cathedral. On his death, his illegitimate son Harold I, seized the throne of England. Following the Norman conquest, Winchester Cathedral was erected on the Saxon site of the Old Minster. The Royal remains, including King Canute's bones, along with those of his spouse, Emma of Normandy, were exhumed and placed in mortuary chests around St. Swithin's Shrine in the new building. However in the seventeenth century, during the English Civil War, the bones, after being used by Cromwell's soldiers as missiles to shatter stained glass windows, were scattered and mixed in various chests along with those of some of the Saxon kings, including Egbert of Wessex, Saxon bishops and the Norman King William Rufus. The chests remain today, seated upon a decorative screen surrounding the presbytery of the Cathedral.

Scientists from Bristol University now plan to examine the skeletal remains of Canute, Queen Emma and their son Harthacanute, along with other kings, including the Saxon kings Egbert and Ethelwulf. The chests have been placed in the Lady Chapel of the cathedral to allow examinations to be carried out without removing them from consecrated ground. A Heritage Lottery Fund grant has been applied for to finance the project. Team leader Professor Mark Horton has stated 'The preliminary findings are very exciting.' DNA may be compared with that of Sven Estridsøn, Canute's sisters son, who was buried in Roskilde Cathedral in Denmark in 1074/76. His remains were intensively examined and his face reconstructed a few years ago.